As the chief White House ethics lawyer from 2005 to 2007, my job included screening potential Supreme Court nominees for compliance with ethics rules when they were court of appeals judges. I supervised a painstaking process of cross checking a judge’s financial holdings with every case in which the judge participated to detect any actual or apparent violation of recusal requirements under federal law. Lawyers in my office looked at other ethics issues as well, knowing that if we weren’t exacting in our scrutiny, the Senate Judiciary Committee would fill the gap and confirmation hearings could get ugly. Some judges, who otherwise would have been good Supreme Court picks, for whatever reason, usually relatively minor slipups, didn’t make the “ethics cut.”

Two judges who made the cut, and who otherwise were deemed exceptionally well qualified by the president and his advisers, were Judge Samuel Alito of the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals and Judge John Roberts of the District of Columbia Circuit. I helped prepare both for their confirmation hearings, focusing on the judicial ethics questions likely to be put to nominees by the Senate Judiciary Committee. We covered recusal from cases, gifts and financial conflicts of interest. Both confirmation hearings — Roberts’ in 2005, and Alito’s in 2006 — were almost entirely free of controversy over judicial ethics.

Had Alito made these types of arguments while I was preparing him for his confirmation, I would have told him in no uncertain terms that he was wrong.

Now, 17 years later, I must ask: What happened? My question is not about any one justice but about the entire court. Why today do so many Americans have far less confidence in the ethics of the Supreme Court than we did in 2006?

The problem is that the justices interpret federal statutes that apply to themselves and ethics norms for judges as they see fit. And when their actions depart from generally accepted ethics practices, they claim that as an independent branch of government they can do whatever they want.

Let’s start with gifts from persons interested in cases before the court. It’s been more than 15 years since I prepared Alito and Roberts for confirmation, but my recollection is that I asked both about any gifts, including travel that they could have received from people with interests appearing before them in their circuit courts. Although my concern at the time was free junkets offered to federal judges by corporate-sponsored judicial education programs, the questions I remember asking were inclusive of all trips. After all, I knew senators would ask similar questions at confirmation. As I recall, neither nominee had accepted such trips.

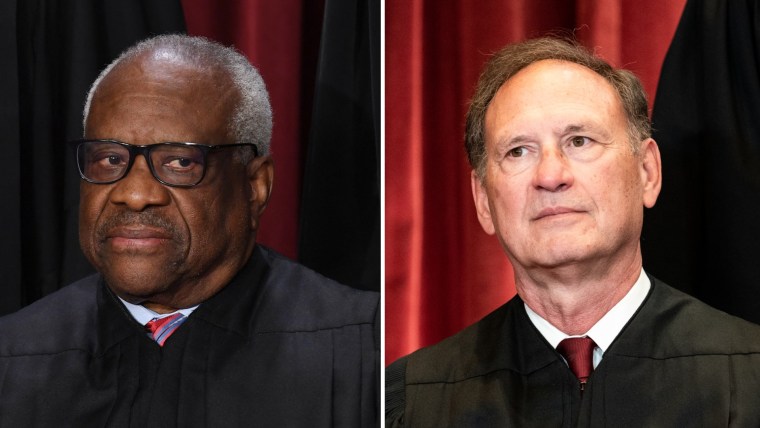

So I was surprised and saddened to read Alito’s defense in The Wall Street Journal of his 2008 vacation with billionaire Paul Singer. As reported by ProPublica, Singer flew Alito to Alaska for a fishing trip, where they were housed at the expense of another conservative donor. In the years since, Singer’s hedge fund had cases before the court at least 10 times, and Alito never recused himself.

In the Journal, Alito argues that he did not need to recuse himself because he didn't have a close relationship with Singer and that he had no reason to be aware of Singer’s connection to any case. He also claims that he did not need to report “personal hospitality,” and that his seat on Singer’s plane “would have otherwise been vacant.”

Had Alito made these types of arguments while I was preparing him for his confirmation, I would have told him in no uncertain terms that he was wrong. In my ethics meetings with senior White House staff, I emphasized repeatedly that free travel on a private plane is almost always an impermissible gift for a government official. Even in the rare instance that it is permissible because the host is a close friend, it must be disclosed. But Alito says that he had spoken only a few times with Singer, meaning Singer was not a close friend, and Alito should not have accepted a free trip on his plane to begin with.

And in any event, the free travel to Alaska had to be disclosed. Alito invokes the “empty seat theory” to say he hitched a ride on Singer’s plane that was headed to Alaska anyway, that it didn’t cost Singer anything additional, and thus was not a gift that needed to be disclosed. This is utter nonsense, of course. In ethics meetings my staff and I also discussed and poked fun of the empty seat theory. No American who is not a Supreme Court justice (or perhaps an ethically challenged governor) can just hitch a ride on a billionaire’s private plane. Try using the empty seat theory to board a plane or a cruise ship without a ticket and see what happens.

The Supreme Court cannot be the only branch of government without accountability to the other two.

No detail in Alito’s defense is as insensitive as his assurance that “if there was wine it was certainly not wine that costs $1,000.” Most Americans splurge when they pay $20 for a bottle of wine and $20 is the limit for permissible gifts in the executive branch. If the trip was so simple and rustic, why didn’t everyone, Alito included, fly commercial and pay their own way? Apparently because billionaires, and Supreme Court justices who interpret the law binding on the rest of us, don’t travel like the rest of us.

This revelation comes on top of controversies about Justice Clarence Thomas’ failure to disclose similar trips paid for by billionaire Harlan Crow even though disclosure of these gifts also was required — not to mention Crow’s purchase of Thomas’ mother's house and payment of tuition for a private school in which Thomas, as his nephew's legal guardian, had enrolled him in. These failures to disclose were inexcusable.

The same goes for Justice Neil Gorsuch. When he sold a Colorado property he co-owned to the head of a big Washington law firm, he needed to disclose the buyer, not just the fact that there was a sale. And it applies to Chief Justice Roberts’ inaccurate disclosure of his wife Jane Roberts’ income as a legal recruiter, including even for big D.C. law firms with cases before the court. Like most headhunters she was paid a commission, not a “salary” — yet a “salary” was how it was described on the chief justice’s disclosure form.

On their own, many of these could perhaps be treated as simple mistakes. But keep in mind that these justices interpret far more technical terms in federal statutes to decide when they do and do not apply to the rest of us. Americans would have more confidence in the court if the justices could at least get their own financial disclosure forms right.

I have written before about how Congress should fix this issue: Pass legislation installing an ethics lawyer and an inspector general for the Supreme Court. The inspector general would investigate and report to Congress on alleged violations of ethics rules by justices and other Supreme Court employees.

Such a law is well within the legislative branch’s powers. Congress already regulates the court by determining the number of justices (there is no constitutional requirement that there be nine), setting the justices pay, and allocating the rest of the court’s budget. And Congress long ago passed the Ethics in Government Act of 1978, which requires the financial disclosure forms filed annually by the justices (as well as senior executive branch officials and members of Congress themselves).

The Supreme Court cannot be the only branch of government without accountability to the other two. Just because the justices hold themselves to a lower ethical standard does not mean the public does. Reform must come, or Americans’ confidence in the court will plunge still further.