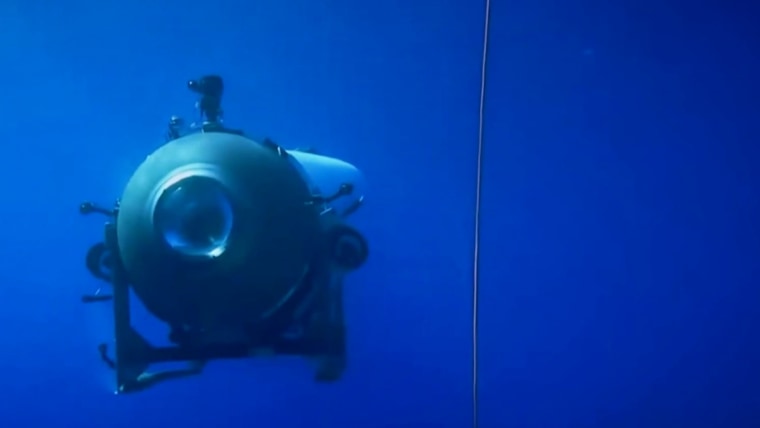

Our anxious wait for news of the five passengers aboard the missing OceanGate Titan submersible expedition is an eerie echo of the anxious wait the world experienced 111 years ago, on April 15, 1912, when an accident on the Titanic was known, but not if all aboard were saved or all lost.

Following reports of a “debris field” discovered by the Coast Guard in the search for the submersible, it is presumed all five passengers have died.

The recreational deep-sea exploration industry is not presently required to meet any internationally recognized safety standards.

I am all for pushing the envelope of human endeavor. As a historian who has studied and written at length about the Titanic, I understand the value of exploration, its intrigue and its promise of unearthing new information about historic events that have so deeply shaped our history.

The OceanGate submersible has opened up new scrutiny on the underwater tourism industry, which is distinct from pure exploration as it includes nonspecialists in these deep-sea missions, making it all the more important to have tight regulation for sub-sea tourism. This is especially important for sub-sea missions at extreme depths like the Titanic’s wreck.

Marine explorer Bob Ballard discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985, nearly 40 years ago, and there have been numerous successful research missions to visit her since then. The present expedition was therefore less exploration than it was tourism, which is a relatively recent phenomenon in the deep ocean.

Like other specialized fields of exploration, such as space tourism, deep-sea exploration tourism comes with many acute and even life-threatening risks. But unlike space tourism (which itself has faced scrutiny for inadequate safety regulations), deep-sea tourism lacks even minimal standards of safety.

This needs to change. All subs carrying fare-paying passengers need to pass certain stringent safety standards. For example, according to one report by an ex-employee of OceanGate, the Titan’s viewing porthole was only rated to a depth of about half that sufficient to reach the Titanic, which is nearly 4,000 meters below the ocean surface.

Only by introducing adequate industry safety standards will we avoid adding further to the Titanic’s already prodigious death toll in the future. Limiting and regulating tourist expeditions will also help to preserve the wreck from too much traffic and damage in the years ahead.

The OceanGate waiver document mentions death three times on its first page and reminds those about to attempt the 3,800-meter descent that the Titan vessel in which they will travel is unregulated.

The disclaimer reads: “The experimental submersible vessel has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body. Any failure could cause severe injury or death.”

But how many of us have “signed our lives away” when committing to do fun and adventurous things? Everything from sky-diving to motor-racing requires this kind of legal waiver. But the difference is that these industries are regulated to a high degree and are required to meet certain safety standards, whereas the recreational deep sea exploration industry is not presently required to meet any internationally recognized safety standards.

What this unfolding tragedy shows us is that perhaps not all those on the sub now, nor others who went down to the Titanic in the OceanGate submersible, really truly comprehended the enormous risks they were taking

I’m quite sure that when businessman Shahzada Dawood and his teenage son, Suleman, signed up to visit the Titanic’s wrecksite in the OceanGate submersible, while they thought they knew the risks, they also believed they were coming back.

We, too, had desperately hoped that they and the rest of the crew would be rescued. But with the final hours of known oxygen supply running out, our hope became ever more desperate.

What this unfolding tragedy shows us is that perhaps not all those on the sub now, nor others who went down to the Titanic in the OceanGate submersible, really truly comprehended the enormous risks they were taking — even though the craft was described by the owner of OceanGate himself, who is one of the missing, as “experimental,” had suffered loss of communication with the surface on previous occasions and was partly constructed from “off the shelf” parts.

In the tragic Titanic sinking in 1912, as the rescue ship Carpathia docked in New York, it was finally revealed that 1,500 people had lost their lives, while about 700 people had been saved.

It seems incredible that, more than a century after she sank, the Titanic still has the power to claim lives today. It’s time we use our knowledge of what transpired that day to better protect people and prevent more tragedies.